Long lines at grocery stores.

Schools no longer open for classroom instruction.

Hospital beds full of dying patients.

Doesn’t all of this sound like the aftermath of the novel coronavirus outbreak?

But these events have happened before — more than a century ago.

In 1918, a virus spread across the world. (Most of the information about it comes from history.com.)

Because Spain was the first country to report news of the illness, it took on the name, “Spanish Flu.” However, the origin of this contagion is unknown.

Spreading to Europe, America and parts of Asia, the Spanish Flu had no cure at the time because antibiotics and antivirals did not exist. All doctors could do was recommend patients take aspirin and rest in bed.

In addition to these circumstances, World War I was a month away from ending when government officials started issuing lockdown orders in Southern California. It also didn’t help much that U.S. troops returning from Europe transmitted the flu even further.

According to a March 16 Los Angeles Times online article, the Spanish Flu consisted of three waves before it finally subsided in the summer of 1919 after the U.S. population reached herd immunity.

Even the leader of the free world at the time, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, caught the sickness but recovered from it — though he never addressed the nation about the pandemic. Nearly six years after the outbreak, Wilson died of a stroke and heart complications at age 67.

Compared to the number of deaths in World War I, which was about 20 million, about one-third of the world’s population was infected with influenza. From this, the estimated number of deaths was at least 50 million people worldwide with 675,000 in the United States.

(As of Memorial Day weekend, the United States remains a few deaths shy of the 100,000 mark from those infected with COVID-19.)

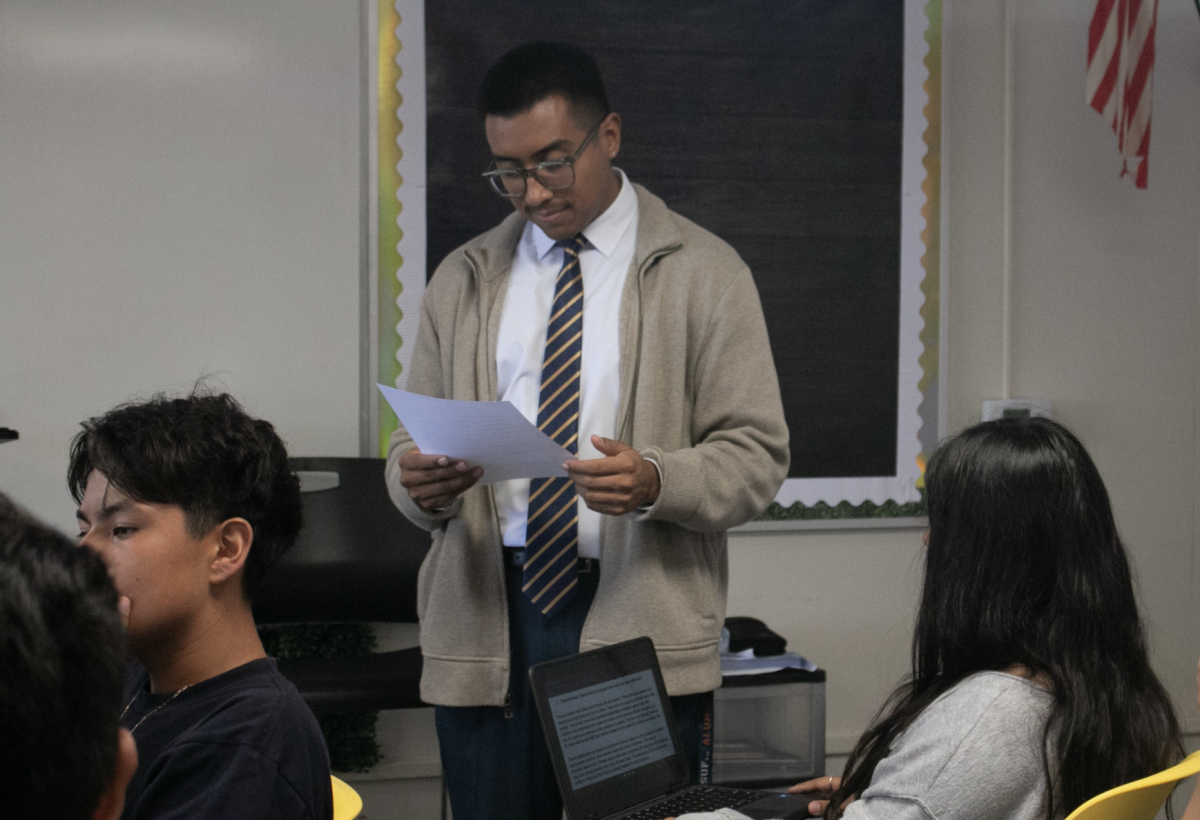

Though Sunny Hills social science teachers say their students do read in their textbooks about the Spanish Flu in their World History and U.S. History classes, many of them are looking at both outbreaks from a more science perspective.

“The whole situation is not so much that history repeats itself,” said Mike Paris, who teaches World History. “It is more that pandemics will happen, and we need to listen to scientists with knowledge on the subject and follow their advice.”

Social science teacher Robert Bradburn agrees.

“We have learned that science is the best way to protect ourselves from this kind of threat,” said Bradburn, who was referring to the science of epidemiology. “People who don’t trust the experts are far behind the rest of the world in their understanding.”

But what about the psychological effect of self-isolation? Can what happened when America opened up again in the summer of 1919 prepare Americans for what’s to come once the country either reaches herd immunity or discovers a vaccine for COVID-19?

“We need to work on our physical and social health,” said social science department chairman Gregory Abbott, who teaches psychology. “What does that mean? Getting exercise.”

While the government has advised since the end of March that Americans remain at home unless they have to leave the house to either work or shop for groceries, Abbott encourages SH students to consider taking walks outside their homes since that has not been restricted.

“Being productive also helps,” he said. “When we are working toward something, our brain secretes dopamine, which improves our mood.”

To maintain a person’s psychological health, Abbott also suggests setting personal goals. Even simple tasks such as cleaning the house and finishing a puzzle can increase a person’s dopamine levels, helping them feel better.

Finally, the psychology instructor wants to emphasize the importance of keeping in touch with friends during this time of quarantine, such as playing games online to pass the time.

“Zoom and similar online chatting apps are not as good as real life, but it does the trick,” Abbott said. “Find a way to do something while socializing.”