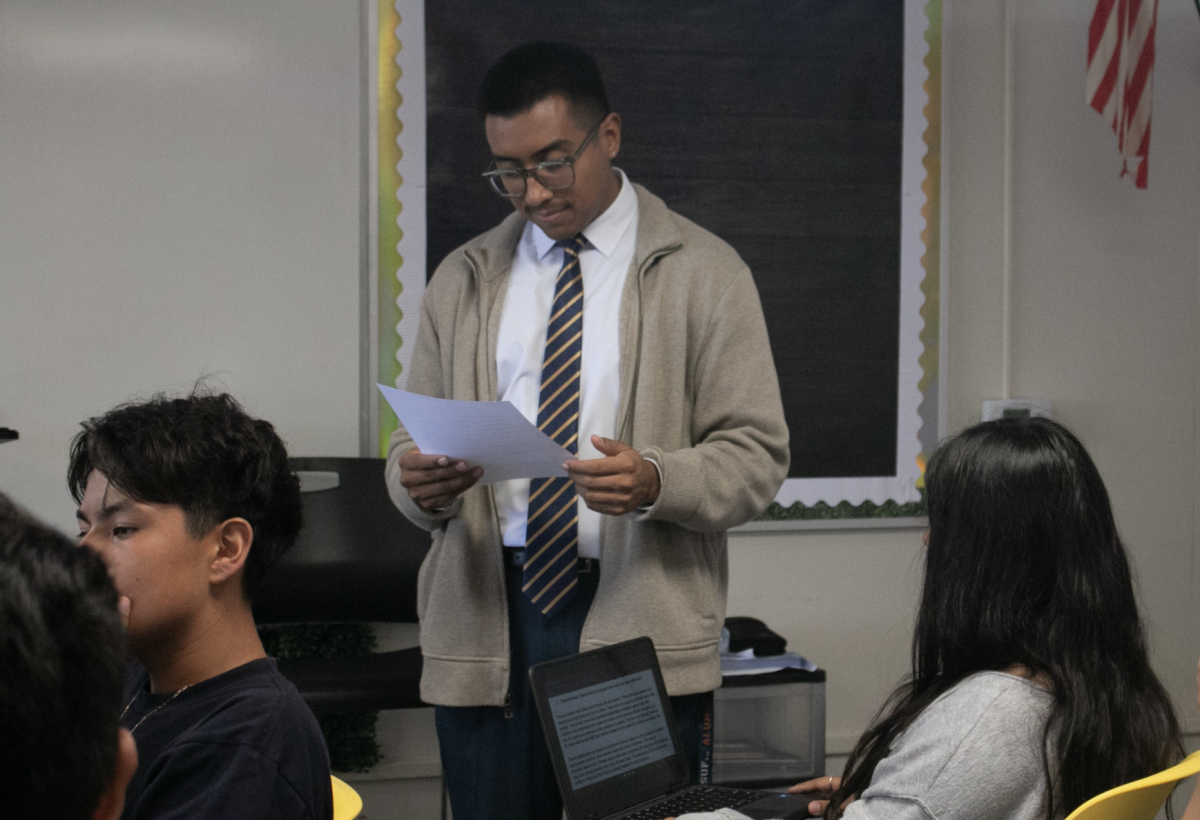

A few minutes before the nearby Fullerton earthquake on Dec. 4, 2023, sophomore Rhea Ji was sitting at her desk, solving problems on a printed worksheet for her Chemistry Lab event at an upcoming Science Olympiad competition on Saturday, Feb. 3.

When the ground began to lightly shake, Ji said she paused, realizing what was happening, and resumed her work once the trembling stopped.

“Since I grew up in California, I never really paid attention to earthquakes unless they came out on the news,” she said. “So when that earthquake happened, I honestly just went on with my night and didn’t really think too much about it.”

Others approach these shakers with a different perspective, especially those studying such natural phenomenon.

“What goes through my mind is a mixture of concern and interest,” said Zachary Eilon, an associate professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who specializes in seismology, tectonophysics and inverse theory. “I first check that I and my family are safe; then I try to ascertain whether there was any damage; then I dive into the data available and try to learn more about the earthquake for my personal and professional interest.”

The U.S. Geological Survey [USGS] records roughly 10,000 earthquakes in Southern California each year — most of them go unnoticed.

However, the five Southern California earthquakes that happened in the last three months have caused some to wonder what fault lines exist in Fullerton, especially if any exist under Sunny Hills.

A TALE OF TWO FAULTS (HERE’S THE FIRST ONE)

On Dec. 4, 2023, at 8:09 p.m., a 3.3 magnitude, which was downgraded from a 3.5 a day later according to USGS, earthquake with a depth of 6.6 miles shook Fullerton. It occurred around 2.64 miles east from Sunny Hills in Fullerton.

The Southern California Earthquake Center [SCEC] studies earthquake processes while supporting research and education in different areas like seismology and earthquake geology. It does this through collaborations with other organizations and joint projects with earthquake engineers.

According to an email sent by the SCEC Community Fault Model Fault Associations to SCEC’s director of communication, education and outreach Mark Benthien on Dec. 4, 2023, at 8:23 p.m. the same day, the association estimated a 43% probability that the earthquake happened on the Yorba Linda Lineament, a fault running from Placentia through Yorba Linda and up to Chino Hills.

Benthien said because of the lineament’s smaller size, the risk of major earthquakes remains minor.

“The Yorba Linda Lineament is too small to have a large earthquake, and it’s not something you should be too concerned about,” he said. “What we need to be concerned about and understand is that there are many other faults that can have earthquakes of many sizes.”

Whether the ground moves because of a nearby fault or a fault miles away, it’s important to be wary of all of them — not just one, Benthien said.

“There are many faults that can have large earthquakes all over Southern California,” the director said. “There’s not some magic place where you can be that’s necessarily better than another.”

HOW IT HAPPENS

Faults are locations with a particular weakness where it’s easier for the crust to break. When stress accumulates on that fault, an earthquake occurs.

Eilon elaborates on the formation of these active areas.

“At some point at the very beginning there must have been an event, some rupture, that created a fault,” Eilon said. “It’s kind of like if you break a toy or tennis racket and then super glue it back together and start using it again — it’s more likely to break in the same place because that’s the weakest bit.”

With that in mind, the associate professor said earthquakes also have an element of randomness.

“Good seismologists do not do earthquake prediction,” he said. “There’s a certain amount of inherent randomness to how earthquakes start and then propagate, and it’s either extremely difficult or impossible to do a big prediction.”

Instead, seismologists do probabilistic forecasting to estimate the chances of an earthquake of a certain size in a certain timeframe, he said.

To then figure out which fault an earthquake occurred on, they use seismic sensors located in different locations to record the vibrations an earthquake gives off.

“We can actually measure the time it takes for energy to travel from the earthquake to the sensors and the speed of the energy,” Eilon said. “We can then work out the distance from the seismic station to wherever that earthquake was; we do this for multiple stations and then draw circles of the distances, and the one place where those circles overlap is where the earthquake happened.”

SO IS SH SITTING ON A FAULT OR NOT? (THE SECOND FAULT)

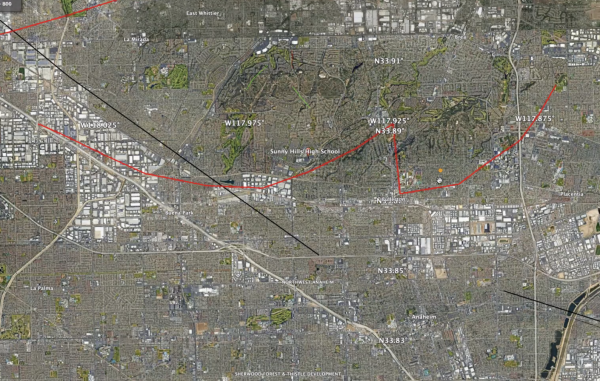

According to the USGS, the Puente Hills Blind Thrust Complex is a fault system that runs 25 miles and consists of three separate segments labeled Los Angeles, Santa Fe Springs and Coyote Hills.

Although it is difficult to determine the exact distance of the fault to Sunny Hills, the Coyote Hills segment runs almost exactly along beneath Sunny Hills.

The system was first identified in 1999 after a 6.0 magnitude tremor 12.4 miles east of Los Angeles on Oct. 1, 1987 – the shake being dubbed as the Whittier Narrows earthquake.

Since then, seismologists have categorized the system as “blind,” meaning the segments are buried under the layers of rock in the Earth’s crust rather than rupturing up to the surface.

“Because the system is blind, it makes it harder for us to find or be alerted by its presence,” Eilon said.

The chance of a 6.7 magnitude earthquake on the Coyote Hills segment, which could cause ample damage, is only at 1% average in the next 30 years, Eilon said

Michigan Technological University defines a 5.5-6.0 magnitude to have slight damage to infrastructure and a 6.1-6.9 can cause a lot of damage in populated areas.

“There are uncertainties in the chances, but it means that every year there’s maybe a 30th of a percent chance of a 6.7 earthquake hitting that fault,” he said. “This is not that big, so you don’t need to be worried every day you go to school, but it’s something the school should be prepared for.”

The chance of an earthquake occurring directly under Sunny Hills is still a possibility, the associate professor said.

“Theoretically there could be an earthquake directly beneath the school,” he said. “Note that large earthquakes do not occur at a single point in space but involve rupture of some patch of the fault.”

According to an April 2003 article published by Science, the Puente Hills system itself is still classified as active, and seismologists estimate four large earthquakes on the fault in the last 11,000 years, with the most recent set being between 200 and 300 years ago.

Despite the rare chance of such a large rumble in the nearby fault line, a March 2017 report by a team of scientists from USC, Harvard University and UCLA shows how the Puente Hills system fault’s speed in which they slip against each other have increased.

Such a bump in the slip rate illustrates the growth in frequencies of earthquakes along this segment over time and the potential increase of safety hazards where these faults lie.

“I don’t think the risks have changed enormously, and the fact remains that the Puente Hills thrust system has earthquakes relatively rarely,” Eilon said. “But that doesn’t mean there couldn’t be one tomorrow, or it may be perfectly possible that there isn’t another one for another 2,000 years, but it’s important to think about the risks that come if one does happen.”

According to an April 2014 Orange County Register article, an earthquake on the Puente Hills system could cause around $250 billion in damage and take the lives of 3,000-18,000 people in the Orange and Los Angeles counties.

“I never knew we had a fault under our school,” Ji said. “I’m not really too concerned for a big earthquake, but I think earthquakes in general are something I want to start being more prepared for.”

THE RISKS

Alongside its damaging effect as a whole, if a large earthquake were to happen on the Coyote Hills segment, the shake would create a detrimental impact at Sunny Hills as well, such as infrastructure collapsing and fires, Eilon said.

Earthquakes can easily pose a risk with objects falling and injuring people, prompting the saying to always “drop, cover and hold on.”

“Historically, fires have been very significant causes of damages after earthquakes because quakes can sometimes rupture gas systems and that can lead to fires, so you want to build your buildings really well and have people prepared to react in an appropriate way,” Eilon said.

Liquefaction refers to when shallow properties like soil and sediments, especially those with a lot of groundwater, are shaken and lose their strength and structure, posing a risk.

Although Sunny Hills is not directly a liquefaction risk zone, it can be exposed to incoming liquefaction from other areas such as Anaheim and La Habra, two risk zones. This could cause damaged and fallen buildings and the ground can sink or crack, Eilon said.

Despite the small magnitude of the earthquake in December 2023, aftershocks also remain a prevalent way to enact damage.

“I don’t think people should be particularly concerned [of the December earthquake],” Eilon said. “That said, immediately after an earthquake, there is a slightly higher chance of another earthquake, sometimes a bigger one. It’s basically always a good idea to be very well prepared for an earthquake, especially if you live in an earthquake prone area like Southern California.”

On the other hand, although some may speculate about the inevitable “big one,” referring to a very large earthquake, coming soon, the associate professor said this suspicion isn’t very accurate.

“Many many faults are near LA, and several of them can host large earthquakes; there is no one ‘big one,’” he said. “There is no good evidence that recent seismicity portends an approaching large earthquake.”

The recent small earthquakes felt have all been quite far apart on different fault structures, and because Southern California has a lot of ground stress and deformation, there will always be numerous small earthquakes in the region, Eilon said.

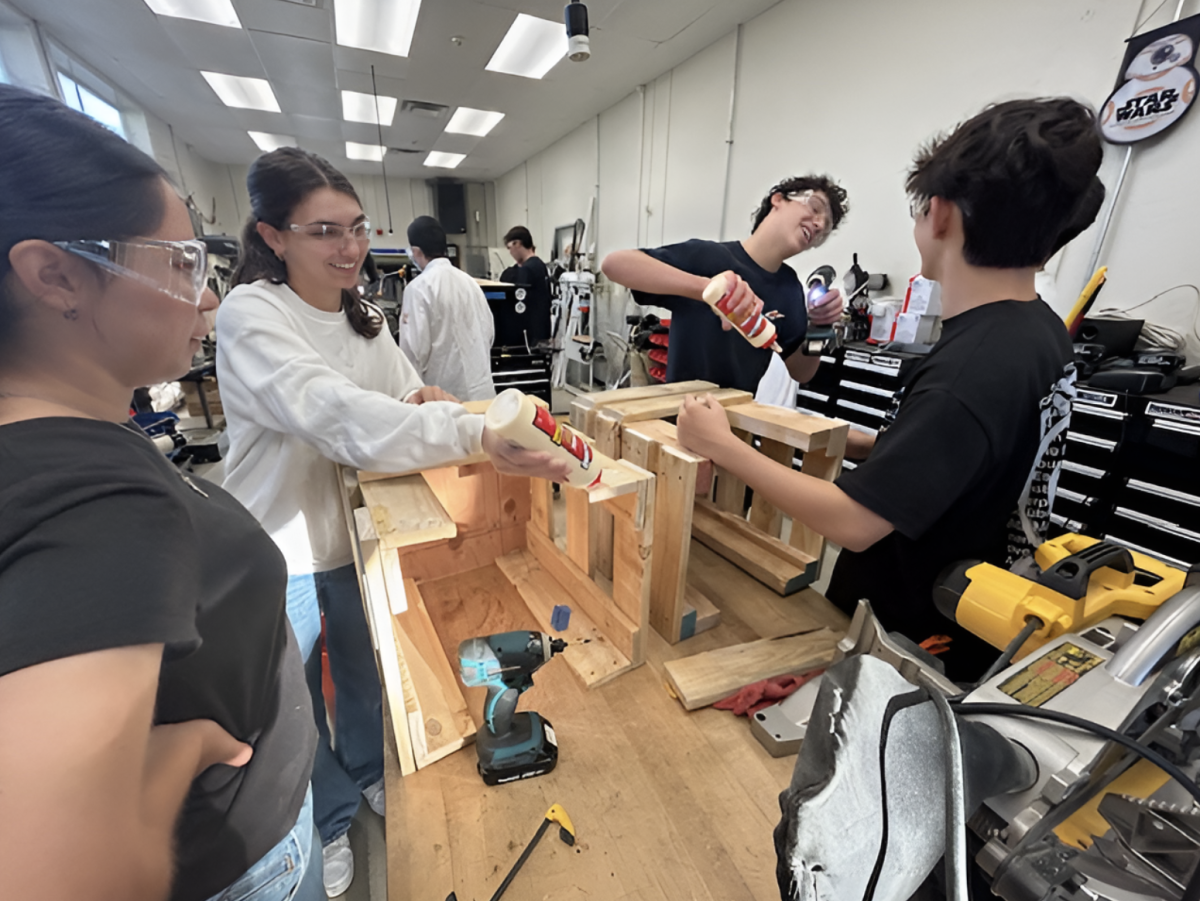

Still, in order to be prepared for this natural disaster, the associate professor stresses some key factors.

“Schools need to make decisions about infrastructure and what they can do within their budget, along with having properly retrofitted buildings with everything up to code,” he said. “Other people in the school, like students and teachers, should also be well trained to react in the event of an earthquake.”

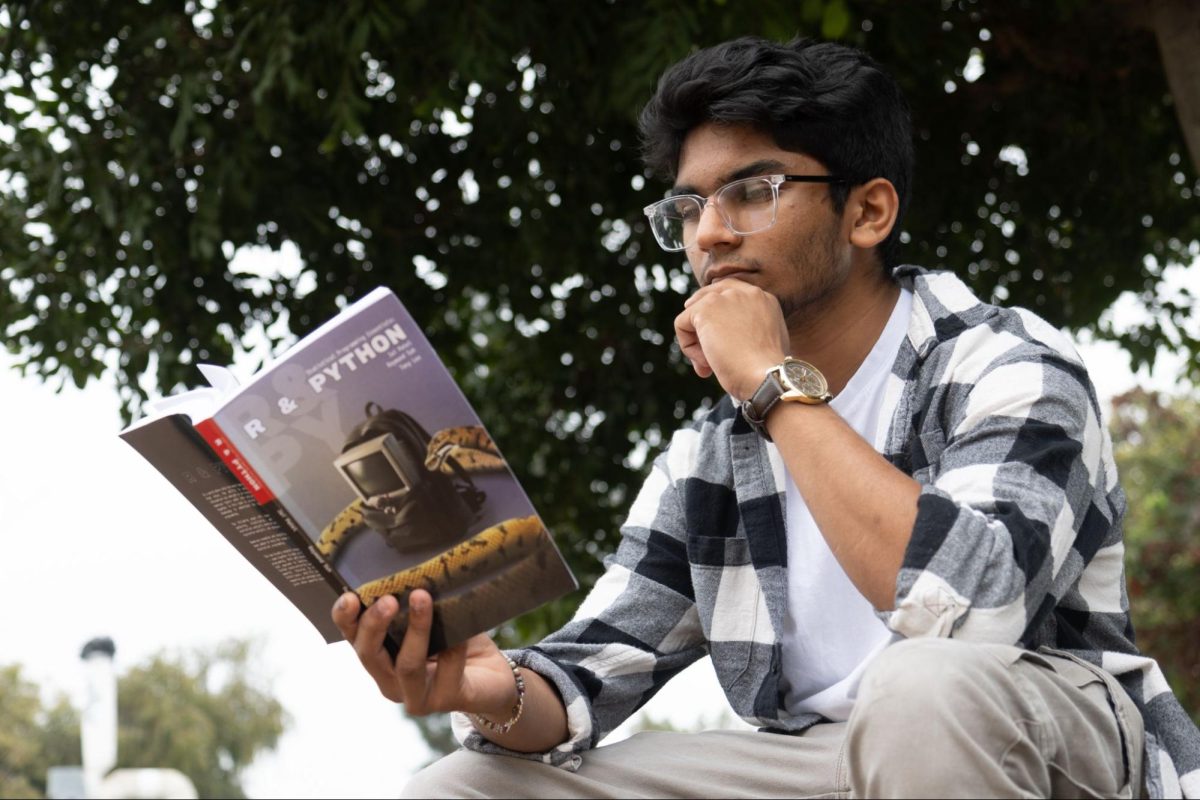

Senior Vicente Cortez shares his own view on California’s tectonic activity.

“I think we should talk about earthquakes more, and people should know about it, but there’s been a lot of small earthquakes where we live, so I feel like we kind of got desensitized to it,” Cortez said.

As an extra precaution, Benthien recommends downloading the MyShake app, which offers the user a 10-15 second notice before a shake arrives.

“They [students and faculty] can have that app on their phone,” he said. “It allows you to get notifications for even smaller earthquakes in your area.”

With these reminders and subtle warnings, it’s crucial for students and faculty to remember the dangers that come along with earthquakes, even while living in Southern California.

“I hope students can take the risk of earthquakes really seriously — that doesn’t mean worrying about them all the time, of course,” Eilon said. “We all live in California and we’re kind of bought into the risk, but it’s definitely something you should have thought about and you should be prepared for.”