The Accolade editorial board vote count: 15 consider a semester-long ethnic studies class becoming a requirement for high school graduation a beneficial addition to students, 2 do not.

Living up to its name, Assembly Bill 101 [AB 101] introduces to classrooms the “101” of cultural history — including the parts that have long been neglected until now. It has become expected for high school students to know the milestones of U.S. history. This is where most students’ knowledge stops, clueless about the history of other cultures.

However, AB 101, authored by California assemblyman Jose Medina and signed into law by Gov. Gavin Newsom Oct. 8, requires public high schools to teach a one-semester ethnic studies class for graduation that will prepare students with a well-rounded historical background on minority groups, according to the Los Angeles Times.

Sadly, implementation of the course won’t affect any students in high school now. High school will have to wait five years before it applies to the first class of students – the Class of 2030.

The plan teaches the “nation’s full history,” as Newsom said in his bill signing statement, educating students about the past of Black, Asian, Latino, Indigenous Americans and other groups that have experienced marginalization in the United States.

As a result, to receive a high school diploma at Sunny Hills a passing grade in the ethnic studies class will be required.

Especially with recent rises in advocacy for minority groups like Black Lives Matter, this class will bring more awareness to these targeted racial groups. This provides an opportunity to dispel false beliefs about discriminated communities or resolve misconceptions that have accumulated over the years.

The closest class to ethnic studies currently being taught is World History in which developments in Asia, Islam and Africa are introduced, according to the course description on College Board. Later units revert back to focusing primarily on the Americas and Europe.

Furthermore, U.S. and European History, heavily centers on whiteness with brief mentions of outside races, according to College Board’s description of Advanced Placement U.S. History. This may have been overlooked in the past, but the increasing diversity in American society, as said by brookings.edu, makes it all the more necessary to stress that Eurocentric influence is not the basis of history.

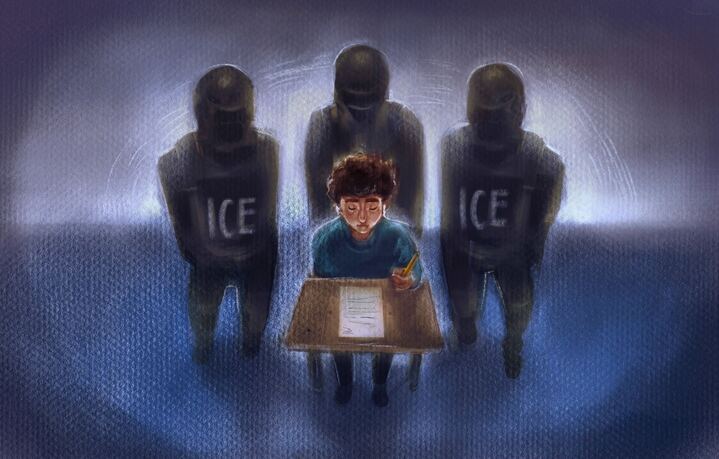

Among the several arguments against the class, opposition to the critical race theory [CRT] — the idea that racism has its roots in legal systems and institutions — led to school board rooms with representatives from boths sides debating the appropriate curriculum.

For example, Placentia-Yorba Linda Unified School District board of trustees debated potentially banning teaching the CRT, according to voiceofoc.org. Some officials argued that it wrongfully targets specifically white figures as oppressors and therefore creates division among the student body.

However, The Accolade believes that an ethnic studies class, rather than creating division, counteracts it. Learning about the ins and outs of other cultures, many of which SH students descend from, manufactures a learning environment that encourages empathy and compassion toward one another.

Regardless of any adjustments that may be made in the future, The Accolade agrees that this educational opportunity will open gateways to learning about the marginalized groups on campus, allowing students to better connect with each other on a deeper level.

The Accolade editorial board is made up of the top editors and section editors on the 2021-2022 staff with the guidance of adviser Tommy Li. If you have a question about the board’s decision or an issue for the board to discuss and write about, please send an email to [email protected]