The famous photo shows children fleeing after the South Vietnamese air force mistakenly dropped a load of napalm (a highly flammable, sticky jelly made from gasoline and gelling agent) on their village during the Vietnam War.

The viewer’s eye is drawn to then-9-year-old Phan Thi Kim Phuc, who is naked in the photo from being severely burned by napalm.

This is Nick Ut’s photograph, “The Terror of War.”

In 2016, Tom Egeland, a Norwegian writer, shared the Pulitzer Prize-winning image on Facebook, which suspended his account and censored the snapshot.

Ut’s photo bears historical significance as a representation of the atrocities of the Vietnam War, but according to a message sent by Facebook to Aftenposten, Norway’s largest newspaper, the photo had to be either removed or blurred because of nudity.

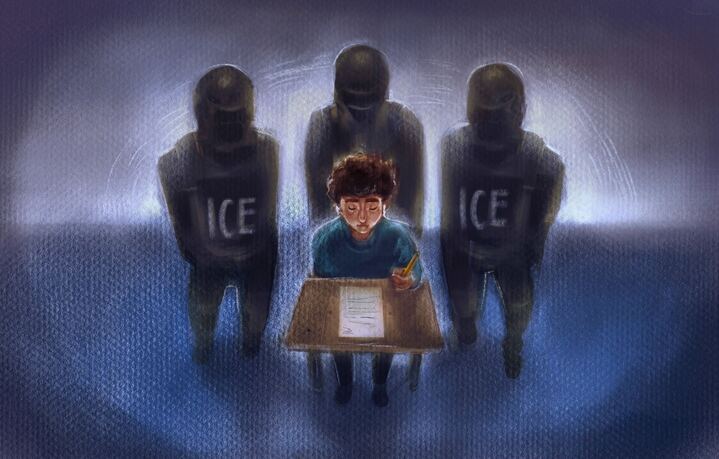

The debate of what social media companies can and should censor has become even more heated after social media platforms Twitter, Facebook and YouTube permanently suspended Donald Trump’s accounts on Jan. 8 following the insurrection at the Capitol on Jan. 6. However, big tech should defend free speech and exchange of thought by making their standards more transparent and enforcing their rules equally among users.

According to a 2019 Pew Research Center study, 76% of Republicans and 63% of Democrats had little or no confidence in social media firms to determine what offensive content should be removed from their platforms.

Legally, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act allows platforms to restrict access to “objectionable content” and gives immunity from what their users post because they are not technically publishers. Many platforms tout themselves as safe spaces for free, global conversations, but on the other hand, they also want the ability to make decisions about what does or doesn’t get published.

According to the Harris Poll/Purple Project in 2019, 63% of Americans would miss freedom of speech if that right was taken away by the government, but CEOs at social media companies like Mark Zuckerberg and Jack Dorsey have immense power to shape the public conversation through deleting posts and banning users.

Trump was banned from Twitter over “incitement of violence,” according to the statement from Twitter, but using that same logic, the supreme leader of Iran, Ali Khamenei, should also be banned for threatening the U.S. and Israel on a regular basis.

One of the accounts linked to Khamenei was banned in 2021 for posting a photo of Trump playing golf in the shadow of a drone with the caption “Revenge is certain” written in Farsi. However, his main English language account remains active.

In a tweet from 2018 that still remains on the platform without any warning labels or flags, Khamenei wrote, “#Israel is a malignant cancerous tumor in the West Asian region that has to be removed and eradicated: it is possible and it will happen.” After Israel’s Minister for Strategic Affairs Orit Farkash-Hacohen called for Twitter to uphold its own hate speech policy and remove the tweet in May 2020, the company’s Vice President of Public Policy Sinéad McSweeney said that Khamenei’s post was “foreign policy saber-rattling” that didn’t violate its policies.

In the blog post “World Leaders on Twitter: principles & approach,” the company states that “if a Tweet from a world leader does violate the Twitter Rules but there is a clear public interest value to keeping the Tweet on the service, we may place it behind a notice that provides context about the violation and allows people to click through should they wish to see the content.”

Yes, Trump is no ordinary citizen — he is the former president of the United States. Platforms should delete posts inciting violence, such as Trump’s and Khamenei’s, and the authors of such content should be held accountable to the law, no matter who they are. But if social media platforms are going to have terms of use policies, the terms should be applied equally to all users and not just the chosen few.

On May 5, Facebook’s independent oversight board ruled that the company was justified in suspending Trump earlier this year, but gave Facebook six months to determine whether he should be permanently banned. The board criticized the company for a failure to state clear rules and explain how it enforces them.

“It is not permissible for Facebook to keep a user off the platform for an undefined period, with no criteria for when or whether the account will be restored,” the board said in its decision. “In applying a vague, standardless penalty and then referring this case to the board to resolve, Facebook seeks to avoid its responsibilities.”

Board Co-Chairman and Stanford University law professor Michael McConnell said that the possibility of political leanings playing a role in Facebook’s original decision to ban Trump is a legitimate concern.

“When you do not have clarity, consistency and transparency, there’s no way to know,” said McConnell after the decision was released. “This is not the only case in which Facebook has engaged in ad hockery.”

Twitter implemented a new policy as of Dec. 16, requiring the removal of Tweets that include “false claims that suggest immunizations and vaccines are used to intentionally cause harm to or control populations, including statements about vaccines that involve a deliberate conspiracy.”

However, Twitter is simultaneously allowing a tweet from Sept. 29 to remain on the platform in which Louis Farrakhan, the head of the Nation of Islam with 347,000 followers, claims that Bill and Melinda Gates and Dr. Fauci are plotting to “depopulate the earth” through vaccines.

Like it or not, social media plays an important part in shaping national opinions. Roughly a quarter of adult social media users in the U.S. say they have changed their views about a political or social issue because of something they saw on social media in the past year, according to a July 2020 Pew Research Center survey. Because social media is so influential, it is even more important for platforms to have a clear-cut, unbiased method of deciding what type of posts can be allowed on their sites.

Although free speech is composed of both “good speech” and “bad speech,” by having opinions of all types available for viewing, users will be able to listen to both sides of an argument and form their own opinions. They will strengthen their critical thinking skills by learning to distinguish between opinions, views or judgement formed about something and fallacies, failures in reasoning, which render an argument unsound.

By banning everyday users from their platforms, citing vague rules and making it difficult to appeal decisions, social media companies may inadvertently cut off the very people who would benefit from being immersed in more mainstream views and fan the flames of conspiracy theories claiming that “big tech” is trying to censor certain viewpoints.

If social media becomes an echo chamber in which users can come to learn one side of every story and reinforce their confirmation biases, the polarization and divisions in our society will only get worse. Social media companies should have the power to moderate all users’ posts for illegal content, but not to the extreme that they are stamping out legitimate opinions that their employees don’t happen to agree with.

As Frederick Douglass once put it, “To suppress free speech is a double wrong. It violates the rights of the hearer as well as those of the speaker.”