Since the coronavirus pandemic forced the closure of live classroom instruction in mid-March and teachers resorted to distance learning and Zoom or Google Meet sessions, I usually muted my video screen unless the teacher instructed me otherwise.

I thought it was not a big deal that my teachers could not see my face.

Of my seven classes that I have each school day this semester, only two of my instructors have ever established expectations that we keep our Zoom cameras unmuted — my Advanced Journalism adviser and my Advanced Placement Chemistry teacher. My experiences in both of these classes have since caused me to have a change of heart about this issue.

Even though fifth period Accolade is an elective, being a staff member means being a member of a family. At least we can see each others’ faces virtually rather than not at all.

As a staff writer, I interview sources, and as I couldn’t interview my Accolade adviser, I decided to talk to science teacher Andrew Colomac during a Sept. 22 Zoom session at the end of second period.

ME: “How were the students’ responses on the first day of school when you did not request to turn on their camera?”

COLOMAC: “I was trying to be friendly and joking, but there were no responses from the screens. There were more black screens on the first day, and it feels like you are talking to yourself in your bedroom or office.”

ME: “How does it feel not hearing any responses from your students in this virtual classroom setting?”

COLOMAC: “It is depressing, You have to understand that most teachers get into this career because they like the interaction with students. We want to talk to people, we want to interact with them, we want to help them.”

At the end of the day, it’s clear that teachers want to get to know the students they will have to teach for the rest of the semester if not the whole school year and deserve more than getting to know 35-40 black rectangular windows.

For instance, if after a difficult lesson students feel confused, teachers can see their befuddled expressions and comprehend that they need to explain the concept some more.

They opt for this career from their love of teaching and working with students, but it is difficult to enjoy this profession if they cannot see who they are teaching.

When students turn on their cameras, they earn their teachers’ trust as well.

For instance, teachers can see that students are “in class” and attending the lecture rather than simply logging on for the sake of attendance and then going off on their own, playing another round of League of Legends or texting their friends or checking their smartphone’s notifications.

Even if students are distracted with their smartphones or video games, their eyes looking off to the side or directly below their Zoom screen exposes what they are actually doing.

At least students can send private chat messages to the educator if they need to temporarily step away to use the restroom or get rid of those annoying younger siblings.

However, teachers also need to understand from students’ perspectives why they choose to not fully engage.

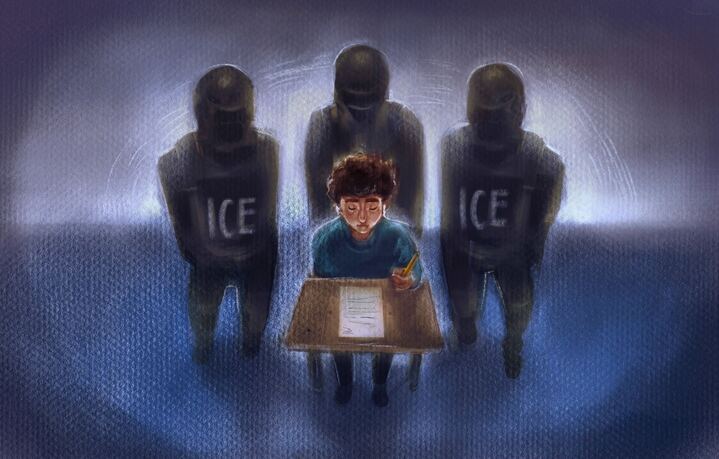

A student’s home atmosphere may be distracting, with rowdy siblings and other family members making guest appearances in the background (that’s me during Period 4). In the case of other students, it may be a personal concern related to embarrassment from what their home learning conditions look like.

They might be horrified that their peers will witness their learning environment, which will hinder them from turning on their cameras. The snowballing pressure resulting from the condition of their homes and the fear of judgment about it can be a reason why students deviate toward showing a black screen instead of their faces.

Some students, even including myself at first, turn off their cameras so their classmates do not catch a glimpse of their family or home environment. My younger brother continuously runs around behind me during class, and I worry that his body streaking on my screen will catch someone’s attention.

In simpler words, students like myself fear that their classmates will judge their homes for being too small and unideal for a proper learning environment.

But these details are irrelevant when the real focus is to learn despite the atmosphere.

Not to mention, family members probably do not like to show up on our camera screens. They might need something at the other end of the room and have no choice but to pass from behind you.

Notifying the carefree siblings, possibly with a physical “do not disturb” sign or a verbal warning every time they are within the camera frame of their learning space might ease the frequent background disruptions as well.

But students are completely certain that their classmates will not judge their family and homes, then they can stop being so self-conscious. This pandemic has put students in a situation where they did not expect to be in, having to learn and unveil their private homes to their educators and peers.

Learning from home means we simultaneously — and unintentionally — share our refuge from school while we are distance learning.

So a message to all students; do not judge someone else’s home environment. No one signed up to have virtual lectures and fried eyes from staring at computer screens for eight hours, so your classmates do not deserve to have their homes judged and scrutinized.

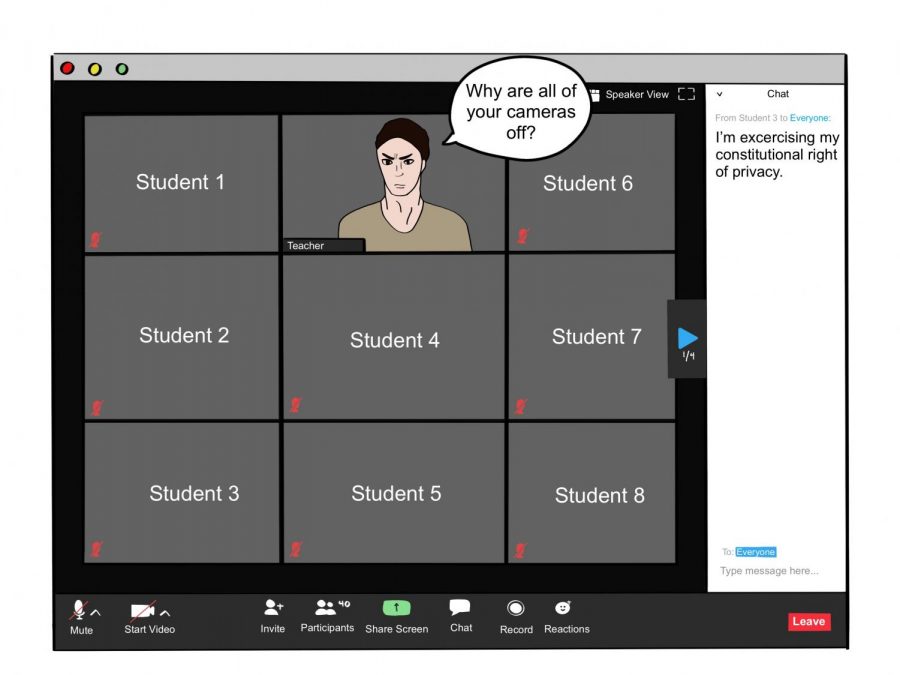

Moreover, social conformity could serve as a potential culprit to blank screens.

When all students have their cameras turned off, and only the teacher’s face remains visible, students who want to turn on their video screens will feel the obvious pressure to stay visually muted.

But it is unlikely that students will reveal their faces if the only two faces visible are theirs and the teacher’s.

A fix to this can prove as simple as contacting friends — through text messaging or another form of communication — in the same class and encouraging them to turn on their screens, starting a chain reaction that will cause more students to follow suit. Setting an example for the class could motivate other students to show their faces once in a while.

This way, the attention will not shine entirely on one person, but it will disperse among the student and his or her friends. Even if only a few students dare to exhibit their faces, no harm comes in joining them.

One month ago, I decided to turn on my camera along with two other students who do the same regularly in my Spanish 2 class in which I only reveal my face on assessment days.

After those 50 minutes went by, I did not feel rattled with my decision. I doubted whether anyone even noticed that an extra face was present in the “gallery” setting on Zoom because we were occupied with taking notes on our lesson.

Every student, including myself, was so preoccupied with the lesson and notes that barely any time remained to notice me daring to show my face on the computer screen.

Since the first day of school, Colomac requests his students to turn on their cameras once the period starts. Although not all students unveil their faces, most students do follow his request until the class period ends.

While the verbal reactions lack their usual energy, he — and let’s hope all instructors — gain one step toward recreating the classroom atmosphere Colomac and his coworkers once had.

“Be nice and make [distance learning] as fun as possible,” Colomac said. “Make [learning] more personal instead of staring at black screens.”

Otherwise if we continue to shield our faces away from our classmates, our teachers have one extra surprise in store for us when we return back to our normal learning regime: what our faces look like.