“If you could change one thing at your school, what would it be and why?”

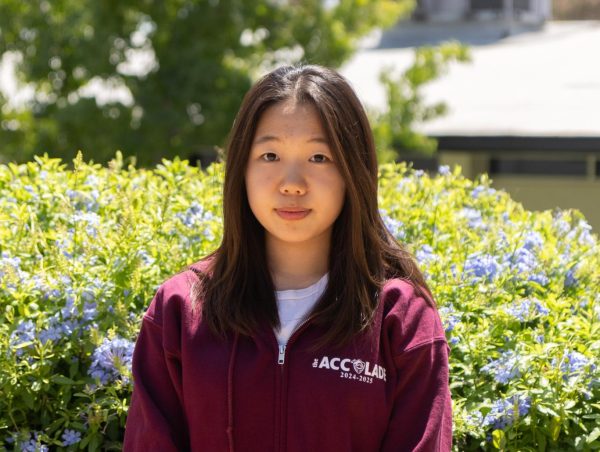

A dozen ideas raced through my mind — mental health resources, school spirit, academic pressure — but none of them stuck. I wanted to choose something I could genuinely speak on, something that resonated. As I searched for the right answer, I realized the question was worth more than a quick response. Seated in a circle of 10 high-achieving seniors — all California Scholarship Federation [CSF] Seymour Award South region finalists — I felt the weight of the moment. Four judges watched from the front of the room, pens ready, listening.

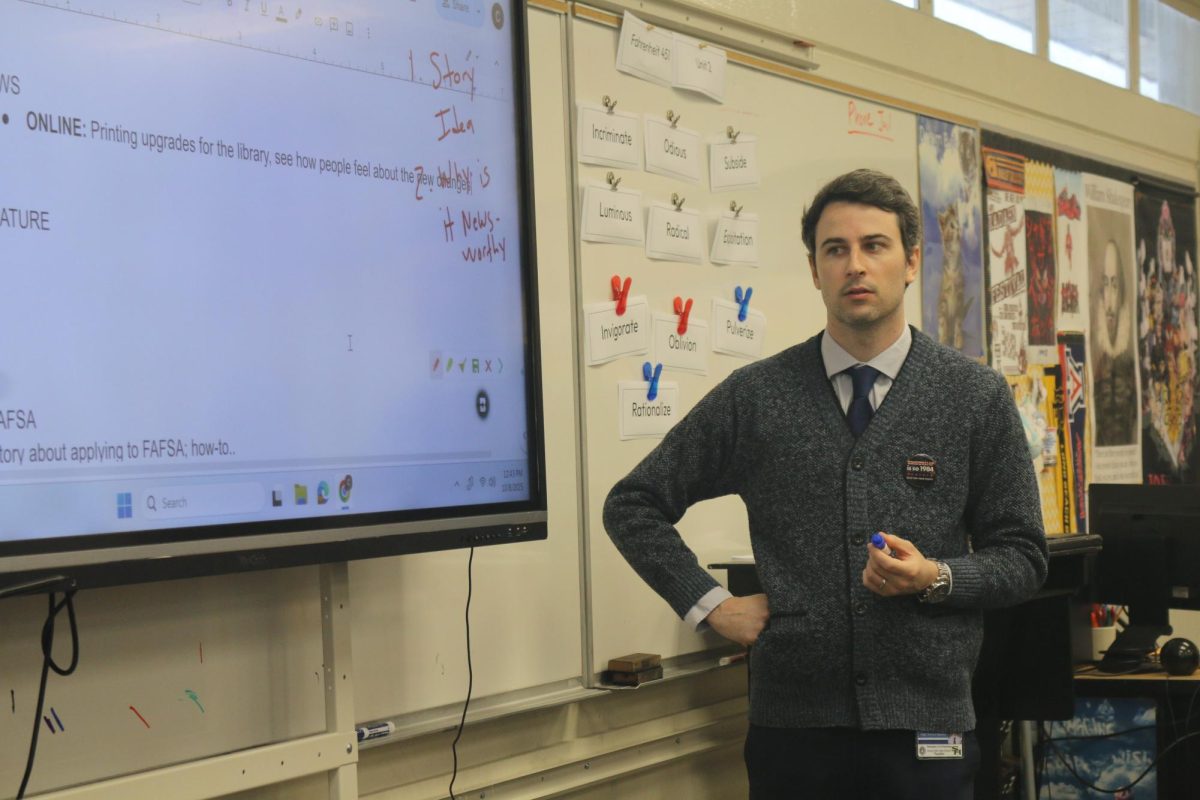

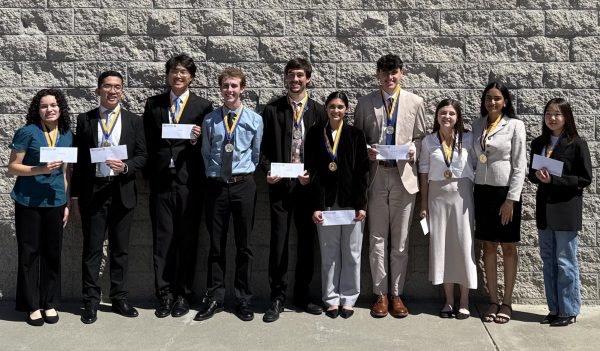

After I had been nominated alongside senior Ethan Hsu by our CSF adviser, social science teacher Hera Kwon, I was invited to represent Sunny Hills at the award interview on Saturday, March 22, at Van Avery Prep in Temecula. Although attending the interview guaranteed us $2,000 each, 1 out of 10 had the chance to win an additional $3,000 scholarship.

I didn’t know this question was coming. None of us did. Well, almost none of us.

A few days before the interview, I reached out to Class of 2024 alumna Hannah Lee — last year’s Seymour finalist from our school — hoping for a hint at what to expect. “Don’t stress,” she replied. She explained how the judges wanted to hear who we were, not just what we’d done.

Still, when I found out it’d be completely unscripted — no outlines, no prep questions, just raw thoughts — my confidence wavered. But ironically, that made it easier to approach the interview since I couldn’t overthink or over-prepare.

So when the judge asked, “If you could change one thing at your school, what would it be and why?” I paused, letting the question sink in as my mind flipped through possible answers.

But then, almost impulsively, I raised my hand and said, “I wish our school didn’t have so many clubs.”

It’s not something most people expect to hear, especially at a school that prides itself on involvement and leadership. But with approximately 130 clubs at Sunny Hills, I’ve noticed that many are eerily similar or aren’t as active as they should be.

While some clubs are genuinely active and meaningful, others seem to exist just to give students “founder” or cabinet positions. It’s a cycle: a new club forms, officers are given to friends, and after Club Rush, efforts diminish.

I experienced this myself as a cabinet member of a club that fizzled out within weeks. Despite having a leadership title, I was left with no direction, no responsibilities and no communication. It became clear that the purpose of the club wasn’t to create impact — it was to check a box. That experience made me more conscious of how leadership roles can be misused, and it pushed me to approach my own club involvement with more intention.

As the president of the CSF, Leo Club and Health Occupations of America and founder of the Health Sciences Club, I’ve seen and experienced how hard it is to run a club that actually serves a purpose and differentiates itself from other numerous organizations on campus. That’s why I suggested that schools like ours need a stronger approval and renewal process: one that ensures new clubs are offering something unique and that existing clubs stay active and involved.

Of course, I know stricter requirements could discourage some students from starting clubs. But I don’t think the goal should be to stop people — it should be to support the ones who are serious. With the proper guidance and criteria, students can still pursue their ideas while making sure their efforts lead to something more than just a line on a resume.

But then I heard the other students speak.

One of them casually mentioned his school had around 400 clubs. Another chimed in with examples like the Crumbl cookie club, Karaoke Club and the Balsamic Vinegar Aficionados club. Their tone wasn’t mocking but rather proud. To them, having hundreds of clubs meant more creativity, more community and more opportunities.

That forced me to rethink my stance and our school environment. Reorganizing my opinions, I wanted an environment where we had diverse opportunities opened to students rather than overloading ourselves with solely academic or community service-oriented clubs.

Frankly, it would be a breath of fresh air to see a Karaoke or Crumbl club have a stand at the Club Rush, and I have no doubt that it would surely stir up some conversation, considering the academically saturated club environment our campus culture possesses.

Hearing the other finalists’ responses made me reflect on how schools define leadership. Some students wanted to change the bell schedule back so schools would start earlier. Others focused on school culture and the spirit on campus. Each answer felt like a mini editorial — a glimpse into what mattered most at their schools.

And that reminded me: At The Accolade, we ask this same question every year when we plan our staff editorials. Last year, when 39 seniors were named valedictorians, we questioned whether that number diluted the meaning of the title. We’re constantly debating what needs to change, whether it’s in our school’s policies or in our own newsroom.

That’s why this experience mattered to me, and I feel utterly grateful to attend, not just for the scholarship but for the discussion and connections I made with the high-achieving seniors and the CSF judge committee. Speaking in such a setting where I conversed with students from other high schools — like those in Temecula, Huntington Beach or Menifee, just to name a few — I would have never gotten a chance to interact with them, and being able to share our personal experiences, perspectives and opinions meant a lot.

Looking back, I ask myself this question: Would I still choose clubs if I were asked that question again? Maybe. Or maybe I’d suggest something new like a dedicated space on campus to showcase student achievements, from academics to athletics to the arts.

Although I didn’t walk away with the biggest check, I walked away with a bigger perspective: Leadership isn’t about starting something — it’s about knowing why it matters.