In sixth grade, I first overheard this phrase passing by a lunch conversion: “Asians get A’s because they’re not ‘B-sians’ or ‘C-sians.’”

After processing it for a second, the underlying message behind it shocked me.

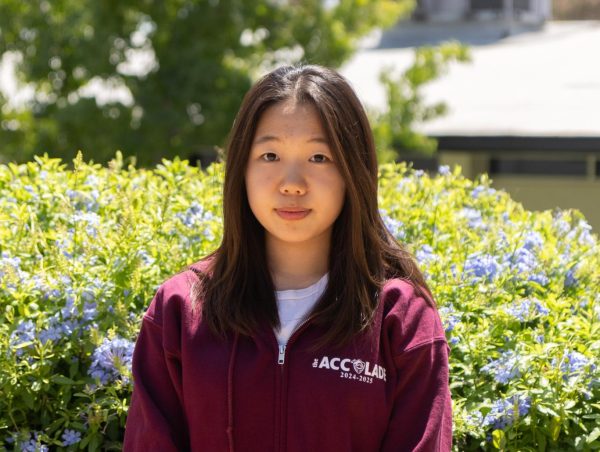

Growing up, I experienced many different environments because my family moved from South Korea to Michigan in fifth grade for a few months, to San Jose and to Fullerton in eighth grade.

Having to keep up with the fast pace to learn ahead of what’s being taught at school in South Korea, the education system in the States allowed me to relax a bit more, eventually motivating me to exceed with less stress.

I spent my last year of elementary and almost the entirety of middle school in San Jose, where the majority of students were white and Asians comprised about 25% of the school population. Despite being a member of an ethnic minority group, I wasn’t discriminated against or ripped down for my hard work — being in advanced classes and aiming for straight A’s — but encouraged to keep up and work together with peers.

So hearing such a phrase wasn’t insulting but rather funny, especially because it resembled me — an Asian with straight A’s — but I attributed this accomplishment to my hard work, not my race.

Now, having to move to Fullerton for the last couple of months of eighth grade was a shift. Although my parents knew the academic environment was going to be different, learning that Robert C. Fisler School had honors and pre-Advanced Placement [AP] classes and informational flyers for parents written in English and Korean — not English and Spanish — was shocking itself and marked the distinction in the academic environment and culture.

I kept up with the differences in the academic culture and competition by managing to motivate myself to get involved instead of my parents pushing me into everything. Thus, before my freshman year, I decided to email the journalism adviser to learn how to get into The Accolade and the band director to audition for Symphonic Band to continue playing flute in high school.

After spending two years at Sunny Hills, I noticed that overachieving students tend to squeeze in more AP classes rather than taking multiple electives. However, being part of The Accolade and band had greater value to me than competing over how many AP classes I could squeeze in to increase my GPA to as close to 5.0 as possible.

Still taking as many honors and AP classes as I could, I continued to strive for A’s, actively participated in class and got involved in extracurricular activities.

Last year, in my Spanish 2 class, I asked questions to the teacher and tried my best on projects and assignments. Then one of my classmates who had different goals in academics said, “You’re such a try-hard.”

Again, I tried my best to understand the material by participating in class and helping my peers in my math class. I aimed for a perfect A. “Overachiever.”

I’ve been called this a couple of times, and it’s surprising because I didn’t consider myself as such, and I laughed when I heard that.

I found two different motives behind these comments: one, to mock me and my efforts, or two, to compliment me for my hard work.

Because the phrases in both contexts were used in a joking way, it served as a compliment that acknowledged my efforts.

However, the phrase “teacher’s pet” is a different case.

According to grammarist.com, “Calling someone a teacher’s pet is an insult; it implies that the person does not deserve his high status and has an unfair advantage. In this case, the word “pet” refers to a pampered or spoiled person.”

Hearing “teacher’s pet” even as a joke implies that I frantically want the teacher’s attention to gain some advantage, which I do not — I was just seeking clarification to help my learning outside class time. If “try-hard” was a way to recognize the effort, “teacher’s pet” was the phrase that seemed to mock my intentions harshly.

Diverse groups of people exist in most settings like schools, and some people think that taking AP and honors classes is too much, while others consider them as normal. At Sunny Hills, a school ranking in the top 1,000 in the nation with an AP participation rate of 66%, according to the U.S. News and World Report, I encountered more who strive for excellence and seek reward through getting into prestigious colleges, while some chose to stay in regular classes with their differing intentions.

Still, with the heated educational environment, I loved the challenges and meeting classmates who had similar academic interests and goals. Moreover, I wanted to gain experience in diverse areas through engaging classes and extracurriculars starting in high school.

Those who have different goals for high school and the future may think I’m a “nerd” for wanting to take on the rigor and responsibilities. And this results from the clashes in different standards people set.

I am a self-proclaimed perfectionist. With the expectations I set for myself, I want to maintain high grades, juggle various extracurricular activities and still set aside some time to socialize.

The upward trend of maladaptive perfectionism — setting unrealistic expectations with low self-esteem and high self-criticism — continues its prevalence as the competition gets more intense over the years. The increasing pressure to exceed peers to some degree through academics and extracurriculars is profound, making it challenging to go beyond as years pass.

A lot of students taking AP, International Baccalaureate and/or honors classes that I’ve talked to had experiences with obsessively stressing over tests, struggling with mental health even without noticing at times and sacrificing time to sleep and socialize with friends. I, taking multiple AP and honors classes, also did undergo those circumstances; yet, a lot of students don’t acknowledge the time they spend behind the scenes to maintain good grades and balance activities.

This relates to the duck syndrome: all the hard work pedaling to stay afloat remains underwater while they present their excellence gliding on the surface.

As such a trend continues, I also felt that my hard work can be trifling compared to those who constantly paddle underwater to meet their own overachievement standards.

Although the comparisons and the “toxic” culture often result in adverse mental health, peer pressure and low self-esteem, it still tends to motivate students to become “academically successful” to reward themselves in the end.

School settings encourage people to do their best and reach their full potential. Recognition programs like the Lancer Awards, Rotary Awards and Parent Teacher Student Association’s Exceptional Effort and Engagement [E cubed] Award aim to encourage and reward students for their academic and community achievements.

As a recipient of a math Lancer Award and Rotary Award freshman year and another one of the former with an E cubed for the community building category the following year, I felt very rewarded with the recognition of the effort I put into the classes and our campus.

Over the past two years, I witnessed some of my peers being nominated for more than one Lancer Award at a time.

While lacking equity and access by allowing one to “take spots” that others could have gotten, the system now is valid as teachers select the students with reasons.

Still, when discussing this matter, one of my friends said the Lancer Award nominations made her feel she wasn’t good enough for the teacher to nominate them. Although invited to the ceremony, she said she was disappointed only receiving the Rotary Award while others received both, if not with multiple Lancer Awards.

Despite the awards’ purpose to encourage higher achievements, it escalates the competition and the societal pressure to prove students’ hard work. The key in describing accomplishments became comparisons — in matters of grades, test scores or extracurriculars — where its value to the individual diminishes.

“Why wouldn’t you want to achieve?” People have different priorities, and it’s OK not to be an overachiever or a try-hard. While aiming and receiving straight A’s might not be the goal for everyone, I will still strive for that title — continuing with the overachieving culture.