“Did you read it?” the classmate behind me in my English 2 Honors class asked his friend sitting next to him.

“Of course not,” the friend replied with a whisper.

We were all waiting for the tardy bell to ring, and the guys behind me were referring to our homework assignment to read a chapter of Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights.

This was my first time attending high school in-person because my freshman year started with distance learning over Zoom in 2020 when we were still dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic.

The boys’ conversation confused me. Of course, when I was attending Robert C. Fisler School as a seventh-grader in 2018, most, if not all, of my classmates would dutifully complete their reading assignments for literary works such as The Hobbit and The Lightning Thief.

So when I overheard these guys admitting to each other that they didn’t do their homework, I was quite flabbergasted.

I had already read my weekly chapter of Wuthering Heights in preparation for our upcoming discussion and looming quiz later in the week. I felt a little frustrated at the fact that I spent a chunk of my previous night reading, and they simply got away with not doing it.

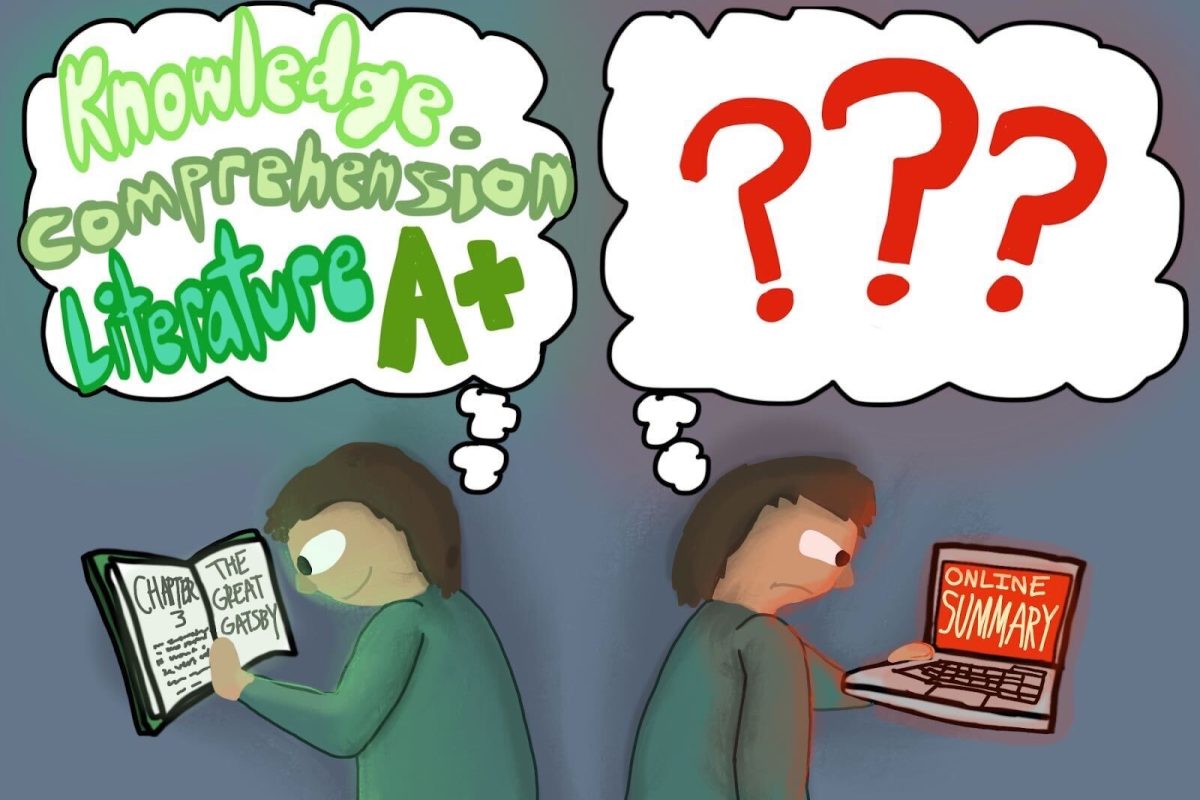

Throughout that school year, I observed that minutes before tests and quizzes, some of my peers would quickly scroll through a summary they found from an online website. This also continued the next year in my Advanced Placement [AP] English Language and Composition class.

Now, as a senior taking AP English Literature, I still wonder about the effectiveness of reading someone else’s summary of what’s happening in each chapter. Has it been this way only since the pandemic? Or has the desire to find a shortcut from having to read 20, 30 or more pages a night been around even before that?

GETTING THE 411 FROM AN ENGLISH TEACHER

I decided to go back to my English 2 Honors teacher to see if she can give me a historical perspective about this issue. Boy was I in for a surprise, as I found out the shortcut method had been an option for quite some time.

“CliffsNotes.”

That’s what English instructor Christina Zubko uttered when I asked her to help me in my research.

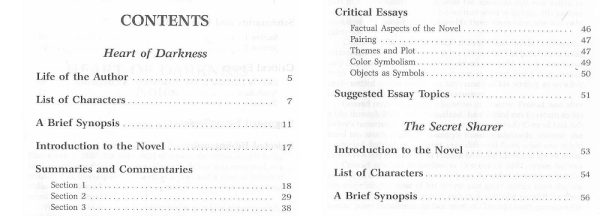

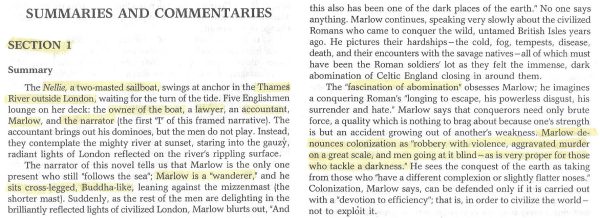

Created in 1958, CliffsNotes provides a collection of summaries and study guides to help students better understand classic literary works. Known for their black-and-yellow striped cover design, the paperback books feature an introduction of the author and novel, a list of characters, summaries and critical commentaries. Today, paperback versions often cost around $6-$10 though many prefer to use its services online.

Zubko explained her opinion on students’ reliance nowadays on Cliffnotes or other such copycat services like Sparknotes.

“Three reasons: They’re not managing their time well — all of our students here at Sunny are just extremely busy. No. 2, they are truly having a difficult time understanding the text because they haven’t been practicing the art of reading. Three, pure laziness.”

While Zubko attests to the fact that the reliance on summaries has been around since the creation of CliffsNotes, she said it’s easier and more prevalent than it was when she was attending high school.

“When I was in high school, we had to actually purchase the CliffsNotes [from a store], the hard copy, and that meant you had to get your parents to buy it and you had to run the whole idea through your parents,” she said. “There were some more safeguards in place.”

CliffsNotes has since gone digital with a website that offers book summaries, character lists, chapter summaries and analysis, character analysis, critical essays, quizzes, glossaries and study help. The cost is $36 per year — or $9 per month — for a subscription to 10 PDF downloads a month without ads.

The service competes with many others that provide the same, if not better, summaries, that are arguably as popular; some being: SparkNotes – probably the go-to resource for most of my peers based on my observations; for SparkNotes Plus, the fee is $24.99 a year – LitCharts ($59.40 a year), Shmoop ($150 a year) and Study.com ($59.99 a month).

Zubko offered this warning for devotees of summary readers:

“The difference between reading the text in full versus reading a summary would be like watching a video of someone surfing versus actually getting on a surfboard and doing it myself, and feeling it.

“You can apply that to golf, you can apply that to tennis, you can apply that to swimming. Even as a writer, you can watch someone write a story, or you can do it. And when you do it, is there more pain? Absolutely. Does it require more time? Absolutely. But the reward is so huge, and you learn so much.”

And she’s right. Thoroughly reading sentences word for word creates a drastically different experience than just hearing pieces of some events in the text.

THE BOOK, THE WHOLE BOOK AND NOTHING BUT THE BOOK

According to an article published by Memoria Press in January 2019, reading literature exercises our imagination, which lessens as we get older. It also provides us with the great tool of being able to see the world through a different lens. Nothing creates more sympathy than actually walking in another person’s shoes.

The most important benefit that I’ve experienced when reading literature is that it makes us more humane human beings. Literature allows us to understand the wild world that we live in.

If students happen to see a problem in our country, they cannot seek a solution without having knowledge on all of the different perspectives on issues. Change cannot be implemented without being knowledgeable about a topic, which is exactly what reading literature provides.

This important activity enhances our ability to contemplate and reflect on life’s questions, while at the same time, it improves our vocabulary and language skills.

Glancing at a brief summary does not train the brain to have all of these crucial abilities, since the book is rarely fully experienced word for word. Disregarding allocated reading can cause a decrease in students’ abilities to read, participate in class and keep up with assignments.

MIXING IN TECHNOLOGY WITH THE HUMAN CONDITION

The accessibility of reading summaries as opposed to reading the assignment text has significantly changed over the years because phones allow students for a quick Google search that provides an entire summary of a particular story, poem or play.

This issue also brings to mind something Jeremy Adams wrote in an August 2019 Los Angeles Times op-ed titled, “My high school students don’t read anymore. I think I know why.” According to him, this generation lives in a small, pixelated world. We will lose our empathy, imagination and dreams without literature amplifying these traits.

Students often disregard actually reading the reading assignments because they feel like the task may be too long or too difficult, which causes them to turn to hurried internet summaries. Thus, many students prefer this option because they don’t take long amounts of time to read, while still providing the most important information.

Most would attest that summaries are also easier to digest than the original material. These synopses can be a helpful short-term solution or serve as a quick review before a test since they focus on key scenes that a teacher might also find valuable and would include in an exam.

However, they are harmful in the long run because students are not fully grasping the text; as a result, they have trouble catching details crucial to what they should’ve read. For example, summaries skim over details, which teachers in more advanced classes include on quizzes or tests.

Some teenagers even complain about how they believe that literature is insignificant, which causes them to question why they should even read it at all.

If a passage feels too long or too difficult, some could benefit from devoting a longer amount of time to focus on it and possibly even reading some strenuous sentences aloud.

Deciding to read an internet summary removes all of the benefits that reading provides, many of which are crucial skills needed in all stages of life.

A SURPRISE TWIST

My research eventually led me to my current English class.

During the second week of school for the 2023-2024 school year, my AP English teacher, Thomas Butler, announced we were going to start reading the play, Hamlet. However, he told us to read a summary of each act every night, and he even provided us with the SparkNotes link on Google Classroom. Everyone, including me, was very excited to have some help reading the notoriously difficult early modern English of Shakespeare.

“Does anyone know why I am telling you to read the summaries before the actual text?” Butler asked the class.

“Is it because Shakespeare is difficult to understand?” one student in front of me asked.

“That isn’t the reason,” my teacher responded.

This left the entire class baffled. Why else wouldn’t we read the actual text first?

He explained we are reading the summaries of each act of the play to understand the basics of the plot, allowing us to focus on the “how” and the “why” of Shakespeare’s methodical literature during class.

The classics, especially Shakespearean plays, are certainly not insignificant, as many of them open the young mind up to the nuances of humanity, produce more empathy in readers about the human condition and act as social or political tools on their own. For example, the classic novel 1984 by George Orwell introduces themes of totalitarianism and censorship to students who are soon to be eligible to vote, teaching them what dangers are possible in society without democracy.

My teacher turning the tables on us by starting with the summary has made me come to the conclusion that platforms like CliffsNotes and SparkNotes should certainly not be relied on but can be great tools to either review or understand classic texts on a deeper level. Online summaries should be treated as an addition, rather than as a replacement to reading the classics.

Hopefully, our future lawmakers, doctors and lawyers haven’t just read summaries of important texts, and if that’s so, we are certainly in for a troubling future.

Cliff Moyce • Sep 14, 2024 at 5:04 pm

Wow. What a great article. I have been reading literature for more than fifty years (!) and have used Sparknotes for years as a way of keeping track of characters, their backstories, and their relationships. I love novels written in the 19th century, but keeping track of all the characters can be a challenge sometimes. Of course, I am reading the full text as well as referring to Sparknotes, and that is the important thing: it’s both, not either/or. It would be such a shame if people used these summary tools instead of reading the full text. By all means use the tools, but use them to enhance the experience, not replace it..