The supply chain: the process through which goods arrive to the consumer, according to Investopedia.

An Oct. 21 Business Insider online article was among the first in the media to spot a break in this worldwide system for delivery goods to consumers. It attributed the damage during the coronavirus pandemic to a shortage in the labor force and reduced availability of storage spaces for imported products.

Then on Oct. 21, President Joseph Biden’s press secretary Jen Psaki made her now famous reaction to the supply chain shortage, calling it “the tragedy of the treadmill.”

A reporter commented on the lack of improvement in the supply chain and the late deliveries for applications such as dishwashers and treadmills, and Psaki commented about the tragedy — suggesting that Americans should start shopping for holiday gifts earlier this year and scolding those who are spoiled and always expect to get what they want.

Biden has since addressed the issue himself, mandating ports, such as the Port of Los Angeles, to be open 24/7, though his administration has not made any announcements about the increasing gas prices.

Despite media reports and political responses, surprisingly, an online poll from The Accolade found that a majority of respondents do not feel affected by the supply chain, while the second-highest majority of voters, 19% of students from the poll, claimed to not have even known about a supply chain shortage at all.

That apparent ignorance has not stopped many teachers in the social science department from sharing their assessment on the matter with seniors in Government or Economics classes.

“Because of COVID-19, there were limitations on how many people could work at one point,” said Greg Del Crognale, who teaches three Advanced Placement [AP] U.S. Government and Politics classes and two regular American Government classes. “There’s so much stuff and nowhere to store it while they wait for it to get on trucks and trains. There are also not enough truck drivers, and that’s what I think the problem is.”

Del Crognale’s assessment relates to a Oct. 25 American Trucking Associations 2021 Driver Shortage Report, which found a 45.45% increase in job openings for truckers now (80,000) compared to 2020 (55,000).

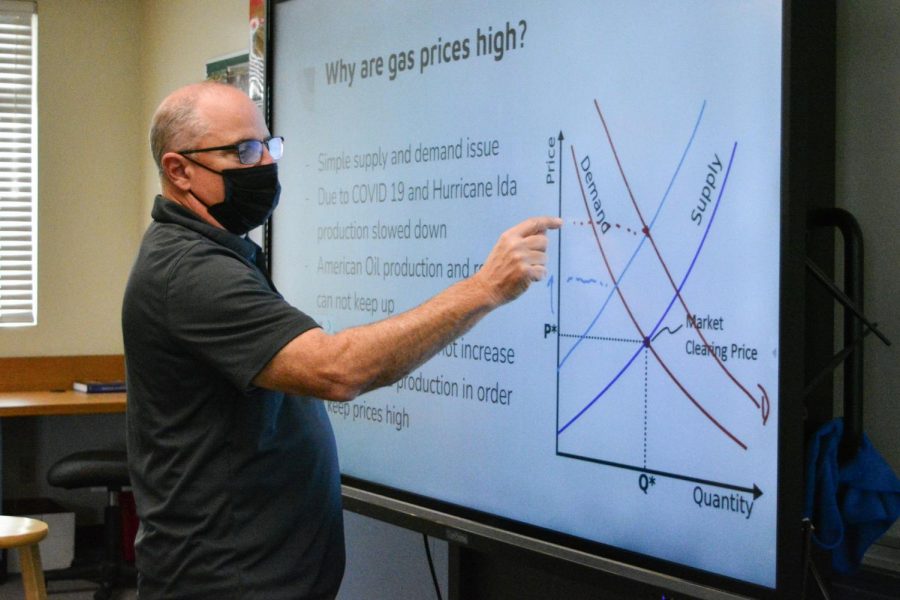

The social science teacher, who also teaches AP Macroeconomics in the spring semester, has also described to his students how the nation currently suffers from demand-pull inflation, which happens when demand exceeds supply.

“People want [too much] stuff,” he said, echoing Psaki’s “tragedy of the treadmill” response. “They didn’t have it in the past, and now they want it. We’re big buyers, and we can’t do without it.”

Social science teacher Robert Bradburn believes that the problem lies in rebuilding the supply chain.

“Workers may have been laid off, so more workers have to be interviewed and hired, which is a slow process,” Bradburn said. “Sometimes, the facilities themselves have been re-purposed or sold. To reacquire the property and the equipment is just very slow.”

Bradburn said he also considers the long-term effects of the declining supply chain, which relates to the current labor issues with 490,000 job openings in the warehouse industry.

“There’s a possibility that some people will leave the labor force permanently, which could lower the growth of the [supply chain],” he said. “And there’s the possibility that [the labor shortage] will create even more pressure for our nation.”

While AP Macroeconomics teacher Peter Karavedas, who will switch to teaching AP Government and Politics next semester, agrees with the others that the labor shortage is an issue, he finds it difficult to believe that Americans are not willing to work.

“The narrative that nobody wants to work is not true,” Karavedas said. “Most Americans are back to work, but [there are labor shortages] in certain sectors of the economy. And the combination in the shortage of those labor markets with the reopening at different times has created some supply chain issues.”

He provided possible solutions, which trace back to rebuilding the supply chain through hiring new workers and drivers.

“It will be interesting to see if those types of jobs […] cause us from an educational standpoint, from an economic standpoint to prioritize where we’re trying to guide our labor force,” Karavedas said. “What I mean by that is that we need to either train those types of workers better or incentivize those types of workers if this is going to be a foreseeable problem in the future.”

However, economics teacher Keith Nighswonger claims that the root of the nation’s inflation is the country’s greener approach toward solving the climate change crisis.

“Energy is a big part of this inflation that we’re going through right now,” Nighswonger said. “Here’s the thing: everybody is for a clean environment, so there’s no way you’re gonna find one person that doesn’t want a clean environment. But are you willing to pay $5 for a gallon of gasoline?”

Many economic teachers have taught their students about the supply chain, including Bradburn, and students such as senior Edward Cho, who expressed interest in pursuing a career in economics, have formulated their own opinions about the matter.

“While our teacher did not mention specifically about the current supply chain issue, we learned about what happens when supply decreases,” said Cho, who is taking Economics IB HL-2. “I agree with what Bradburn said about it affecting me and my community.”

He explained how he has observed a demand-pull inflation with the increase in prices with a lack of supply and increase in demand.

“Cars are a good example of it,” Cho said. “Many brands are adding markup values to their cars. But this is all in the short run and in the long run, the economy will reach back to the long-run equilibrium.”