When Class of 2022 alumna Rachel Lee first opened her Harvard University acceptance letter in December 2021 through an online portal, she was greeted by the word, “Congratulations!” in bold text.

After applying to the school under restrictive early action, a non-binding admissions process that limits a student in applying to other schools’ early action programs, Lee had gotten accepted into one of the most prestigious universities in the country despite its record low acceptance rate that year.

However, curiosity immediately followed her delight as she wondered why she was admitted among the thousands of other applicants.

Lee couldn’t find the answer to her question until her freshman year at the Boston Ivy League campus.

Though not sure of how she found out, Lee says to have known since her sophomore year at high school that it was possible to view a college admissions file.

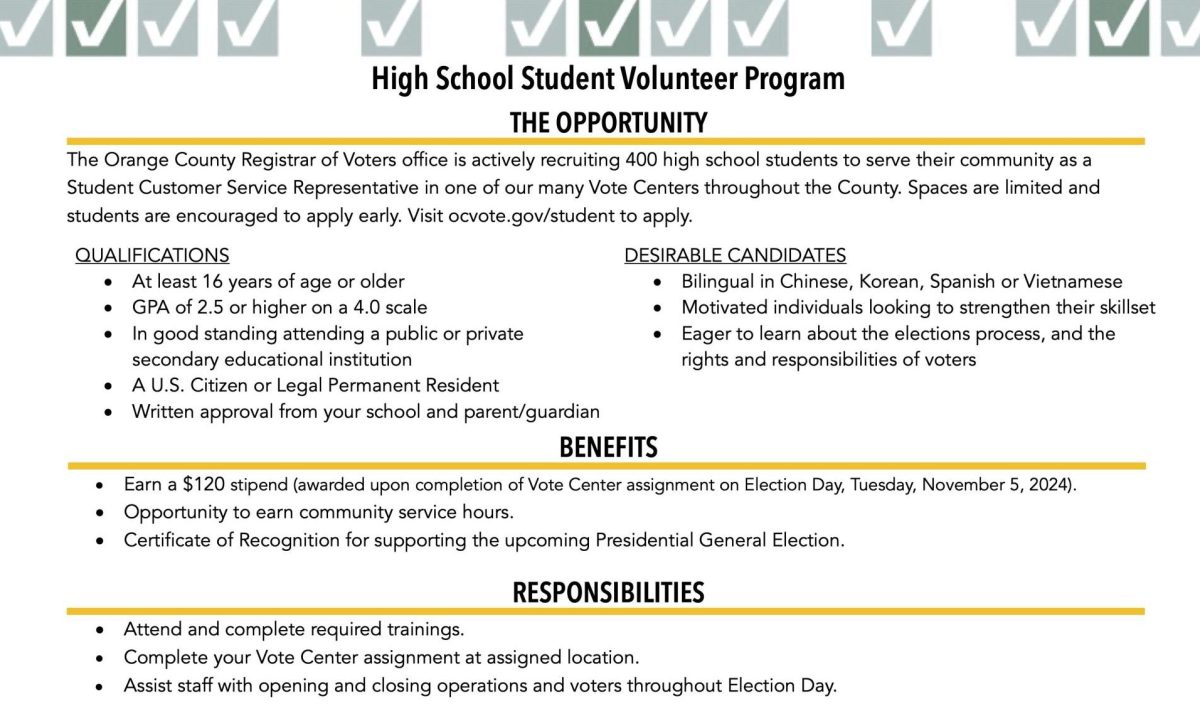

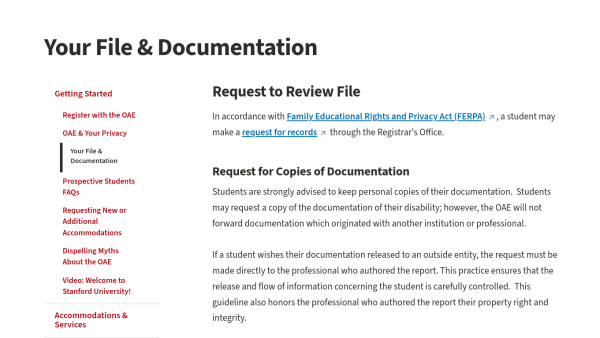

Like Lee, any college student can file a request to review what many universities call an “admissions file.” However, schools are under no obligation to maintain records to a certain level, which encourages many first-years to request it as soon as possible.

Because Sunny Hills campus counselors do not mention that this is possible during information sessions, The Accolade decided to cover this topic in our sixth DID YOU KNOW? feature story.

The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act [FERPA] governs the disclosure of educational records and provides students with the right to view their own information, including their college admissions file.

As 12th-graders fill out college applications, they can either waive their rights to FERPA or leave that blank. If a student waived their rights, then they are eligible to request to see any personal records about them — including teacher recommendation letters — when they start attending the college they decide to enroll in.

The FERPA applies to both public and private schools in the United States.

According to Harvard’s FERPA handbook, students may access their own records through school-regulated processes.

Upon Lee’s first few weeks at Harvard, she decided to file her request to view her file through Harvard’s admissions department.

“I just wanted to see it so that I can better understand the admissions process because it’s something I’m interested in,” she said.

Though she has declined to comment about the contents of her file, she said that it was helpful to read the notes from admissions officers who had reviewed her application.

“It’s important to know what your weaknesses are and how you can improve on that,” she said. “Even if you feel like you don’t belong, you’re here either way, so you just have to believe in your own abilities.”

A few weeks after requesting her college admissions file information through an online form, Lee said she received an email with a PDF of her admissions information attached to it.

“I found out that Harvard, like many other schools do, ranks their students from 1-6 in different categories, like academics and extracurriculars; lower numbers are better,” the neuroscience major said after reviewing the PDF file. “One thing that is surprising, though, is everyone’s scores are pretty high, and that’s just the way it is because the process is so competitive.”

The lowest number tends to be reserved for Olympic athletes and world-recognized scholars, so most applicants get numbers like twos, threes or even fours, Lee said.

Class of 2019 alumna Camryn Pak also never knew about this option until she started her first year as an American Studies major at Stanford University.

During her first week on campus in the dorms, several of her peers told her she could view her file, and she wanted to do the same.

“I was curious about what admissions [officers] liked about my application,” said Pak, who graduated from Stanford University in June with a bachelor’s degree in American Studies and is currently pursuing her master’s degree in communication at Stanford. “I had an idea of how I wanted to present myself as an applicant, but I was curious as to how they perceived me.”

After requesting to view her file through an online process, Pak said she received a link in an email response in which she was able to sign up for a 20-minute appointment to view her application in Stanford’s Student Union building.

“It was in PDF form, and a fair amount of information was redacted,” she said. “I was allowed to bring a pencil and paper to write things down but was not allowed to have my phone.”

Like Lee, Pak said she was rated in different categories, such as intellectual vitality and extracurriculars, on a numerical scale from 1-6, with the lower number being the higher score.

“My overall score from both readers was a 2,” she said. “I don’t know anyone who was admitted to Stanford with an overall score higher than a 4.”

Pak had two sets of statements from her application’s two readers, who commented on her stated academic interests, class ranking and parents’ countries of birth and occupations.

“They also wrote a note that said ‘READ!!!!!!’ on my intellectual vitality essay, so I guess that one might have been what really caught their attention,” she said.

Her second reader agreed with the comments left by the first one, referring to her overall application as “one to keep,” Pak said.

Lee and Pak read comments left by their university’s admissions officers, but neither were given access to their high school teacher recommendations after waiving the rights on the Common Application.

“I waived mine because I read online that if you don’t, it could potentially harm the credibility of the recommendations. I think it was something everybody did,” Pak said. “I didn’t really think twice about it, since I knew my recommenders wouldn’t have agreed to write letters for me if they didn’t have anything positive to say.”

Both alumni agreed that they weren’t shocked by their file because of the brevity and directness of the comments but still recommend others to do the same.

“If anything, it helped with my imposter syndrome and reaffirmed my decision to commit to Stanford. I do believe that the admissions process was holistic and that there wasn’t one factor that ensured my acceptance,” Pak said. “That being said, I think the major components of my application were all solid and gave me a good chance [of getting accepted].”

So for those who feel their college application journey ends upon receiving acceptance or rejection notices, they should know that one more step can be accessible once they start attending the university they get admitted to.

And it’s to review their admissions file.

“If you’re going to read your admissions file, you should be prepared to see both positive and negative comments,” Pak said. “But I think it’s important to remember that regardless of whether you were a borderline applicant or admitted off of the waitlist, you were accepted to your school because you belong there.”