Teacher and student reactions to the recent war in Ukraine have reached a unanimous consensus framing Russian President Vladimir Putin as the aggressor aiming for Russian dominance over its neighboring nation.

“Mr. Putin has made a bad decision,” social science teacher Robert Bradburn said. “Because he’s been in power for so long and because of his age, he may have become isolated from advisers who could counsel him, and he’s become harder in his resolve to make Russia great again. … It may turn out to be his worst decision.”

Junior Chirag Agarwal sympathizes with the victims of the Ukrainian invasion and recognizes the global repercussions of Putin’s military orders.

“Historically, we noticed patterns which showed that when any country was looking to expand its territorial ownership, there was also a war,” Agarwal said. “This again, is happening in the 21st century, and I am just very frustrated.”

ORIGIN OF RUSSIA’S AGGRESSION

Ukraine declared its independence from Russia Dec. 1, 1991, as the communist-led Soviet Union began to collapse. Upon his first inauguration held May 7, 2000, Putin has been working toward reasserting the nation under Russia’s dominion, according to various media reports.

He took his first steps with the illegal annexation of Crimea, a Ukrainian peninsula located between the two nations, in March 2014. By seizing the peninsula, Russia displaced nearly millions of citizens and amplified the tension with its neighboring nation.

Beginning April 2014, Putin stationed his troops in Donetsk and Luhansk, two eastern Ukrainian cities within the Donbas region, to regain the territory essential to keeping the nation in line with Russia’s geopolitical demands — supposedly to show support for the pro-Russians living in that area.

By November 2021, Putin escalated his pursuit for that western neighboring nation by mobilizing tens of thousands more troops along the border, according to Aljazeera.

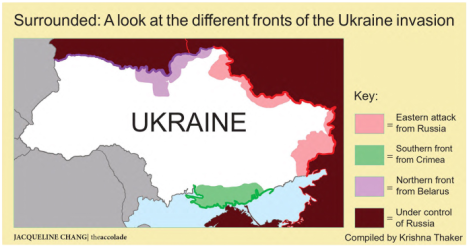

Based on media reports, Putin launched a full-scale invasion on Ukraine on Feb. 24 – four days after the closing ceremony of the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics held on Feb. 20.

He then ordered missiles to strike in Belarus and sent tanks accompanying nearly 200,000 troops headed for the Ukrainian capital — Kyiv. Convoys of troops and tanks also entered from Crimea, which shares a southern border with Ukraine.

To the north of Ukraine, the country of Belarus and its leaders decided in 1995 to align with Putin and Russia, which has allowed the Russian leader to fire ballistic missiles on Feb. 24.

According to the Council on Foreign Relations, Russia’s military advancements have led to more than 50,000 estimated casualties and displaced more than 1.5 million Ukranians within the country or to outside European states as of March 2.

“I think it’s pretty obvious what Russia is doing in Ukraine, and it’s hard to see how anyone could be on Putin’s side at this point,” said senior Ian Whedon, one of the students in Bradburn’s third period having in-class discussions about the war overseas. “He’s not sending in peacekeeping forces — he’s invaded the country, and I think it’s telling about how despicable this attack is on Ukraine when Russian soldiers are just putting down their arms and choosing not to fight.”

ECONOMIC IMPLICATIONS OF THE WAR

Responsible for the supply of crude oil and foreign petroleum, Russia holds the power of swaying the U.S. economy, specifically its gas prices and inflation rates in times of political strife, according to Project Syndicate.

“Gas prices have gone up, but right now I am not concerned,” said Del Crognale. “I think people have already seen the high prices and will not be so shocked if it increases a little.”

Russia, on the other hand, is likely to experience extreme economic fallbacks, as the tariffs from the United States and other NATO countries continue to pill on.

“[Russia’s] prices will keep going up for quite a while, and there’s some chance that if Russia’s economy gets terrible, it will have a domino effect,” Bradburn said. “However, their economy is not especially big, so hopefully it won’t cause a ripple effect.”

Bradburn, who teaches International Baccalaureate [IB] Economics and four Advanced Placement [AP] Human Geography classes, does not foresee this war in Europe to take a significant toll on the U.S. economy.

“Our businesses will perhaps have some losses, but that’s not going to affect regular Americans,” he said. “Inflation will affect regular Americans by a lot, but other than that, I don’t see anything that would make it hurt our economy.”

Social science teacher Greg Del Crognale, who teaches three AP Macroeconomics and two American Government classes this semester, shares Bradburn’s perspective about the financial impact of the war.

“[The long-term effect] depends on how long this war drives on,” Del Crognale said. “I think if [gas prices] shot up by double, people would go crazy, but if it’s incremental, I don’t think it’s going to cause that much of a problem.”

AMERICAN INTERVENTION

As Putin’s military continues its assault, many supporters of Ukrainian sovereignty are calling for American intervention in addition to the recent sanctions passed on the Russian banks, government and elites.

In his first statement after the Russian invasion on Feb. 23, President Joe Biden condemned the “unprovoked and unjustified attack by Russian military forces” and vowed to work with NATO allies toward deterring future action against the Alliance.

While it has supported Ukraine financially — an additional $350 million for immediate aid pledged this week for a total of $1 billion in security assistance this year — the United States opposes its physical involvement in the conflict.

On multiple occasions, Biden emphasized that American “…forces are not and will not be engaged in the conflict with Russia in Ukraine.”

That promise has reassured several SH students and staff.

“We are choosing not to get involved because [Ukraine] is not a NATO country,” Del Crognale said. “What we’re trying to do, along with the rest of the world, is limit what Russia can do [without] using air strikes or something, which would lead to World War III.”

Bradburn does not expect the United States to step past its financial intervention by stationing military troops; however, he hopes to avoid such a measure from taking place.

“I don’t think [the United States will intervene], but I don’t know enough about it to be sure,” he said. “But troops of two nuclear powers fighting each other hasn’t happened before, and it seems awfully dangerous.”

Whedon shares his instructor’s judgments and believes U.S. involvement will only result in losses for all parties involved.

“Not only would sending troops to the conflict destabilize the area and possibly escalate into a greater land war in Europe, but doing so carries the weight of a possible nuclear strike from Russia,” he said. “While I wish more could be done, I think the monetary aid the United States and other countries are sending to Ukraine as well as the heavy sanctions being imposed on Russia will ideally be effective means of support while not engaging in direct conflict.”

GETTING STUDENTS TO CARE ABOUT INTERNATIONAL STRIFE

Since Feb. 24 when the war in Europe started, Bradburn said he has allocated the beginning of his IB Economics class and AP Human Geography classes to conducting discussions and updating his students about Ukraine’s current events.

“We have a Sunny Hills poster about what we want a Lancer to be, and we want them to be ready for what comes next, and we want them to participate in society in a meaningful way,” said Bradburn, referring to the Schoolwide Learning Outcomes sign required for accreditation purposes. “Democracy can work, but it takes a lot of people who are willing to participate in it.”

By supplying his students with Ukraine-Russia news, Bradburn found a recurring trend taking place among the reactions of his students.

“They’re individuals,” he said. “Some are very concerned, and they look shocked and horrified; some are more curious, like they’re trying to understand it; some just have other things to worry about, the war is too far away and not affecting them, so maybe they’re less interested.”

Del Crognale observes similar responses from his students as the conflict in Ukraine intensifies.

“There’s some interest in going on because obviously no one wants to go to war and students are young and young people go to war,” Del said. I think most of them are concerned, but I don’t think most understand the magnitude of the situation.”

As an avid participant of such Bradburn’s open conversations, Whedon has formulated a coherent idea of the turmoil driving the conflict between Russia and its southwestern neighbor.

“It’s an IB class, so I think the expectation is that we are interested enough in educating ourselves on geopolitical events as important as this,” Whedon said. “The news articles that he shows us in class are more than enough to talk about, and combined with those of us who are keeping up with any new developments, I think the class, in general, is staying informed on the situation.”

He attributes the thousands of casualties to Putin’s shortcomings as president and admires the Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, for his efforts toward mitigating the war.

“Zelenskyy has also been doing an incredible job pressuring other countries to take action even though Ukraine isn’t part of NATO,” Whedon said. “I think he’s also a major reason why so many Ukrainians are being inspired to fight and resist the Russian invasion, and the fact that the U.N. called a general assembly today, I think, is in part due to him and the amazing leadership he’s shown in this crisis.”

Sophomore Katelyn Fu, who takes Bradburn’s period two AP Human Geography class, uses the social media platform TikTok to educate herself on the war taking place in Ukraine.

“[Bradburn] posted some photos and videos about the war in our Google Classroom, but I get updated mostly by watching the news,” Fu said. “I’m still confused as to why this war is happening though because I don’t think Russia gains anything economically by invading Ukraine.”

Though Fu sympathizes with the Ukrainian citizens, she understands the limitations of the U.S. government’s intervention.

“I don’t want anyone to feel helpless against protecting their basic human rights, but the United States intervening would definitely escalate the situation into a world war,” Fu said. “I’m just hoping the sanctions on Russia are harsh enough because I really don’t want to go to war.”